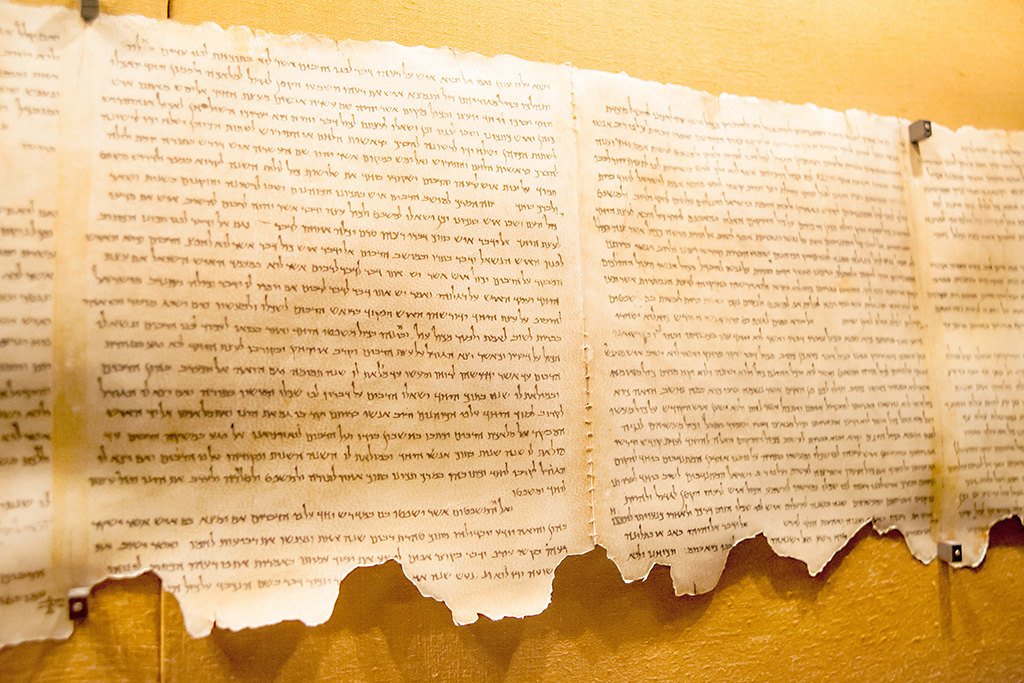

What are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

More than 70 years ago, a Bedouin boy threw a rock into a cave and heard the shatter of pottery. Inside the cave, he and his cousin found seven scrolls, which would later become part of what has become known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. It was the beginning of one of the 20th century’s greatest archaeological discoveries.

Since then, tens of thousands of scroll fragments have been found in caves in Qumran, about a mile from the Dead Sea in Israel. Over the decades, scholars have carefully reassembled them into hundreds of scrolls.

Most people have at least heard of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and perhaps loosely connect them to the Bible. But what do they say? Where did they come from? These ancient documents have been the center of political, academic, and theological controversy, and after years of careful (and in some cases, not so careful) study, we’ve learned a lot about them.

What Scholars Tell Us About the Scrolls

What are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

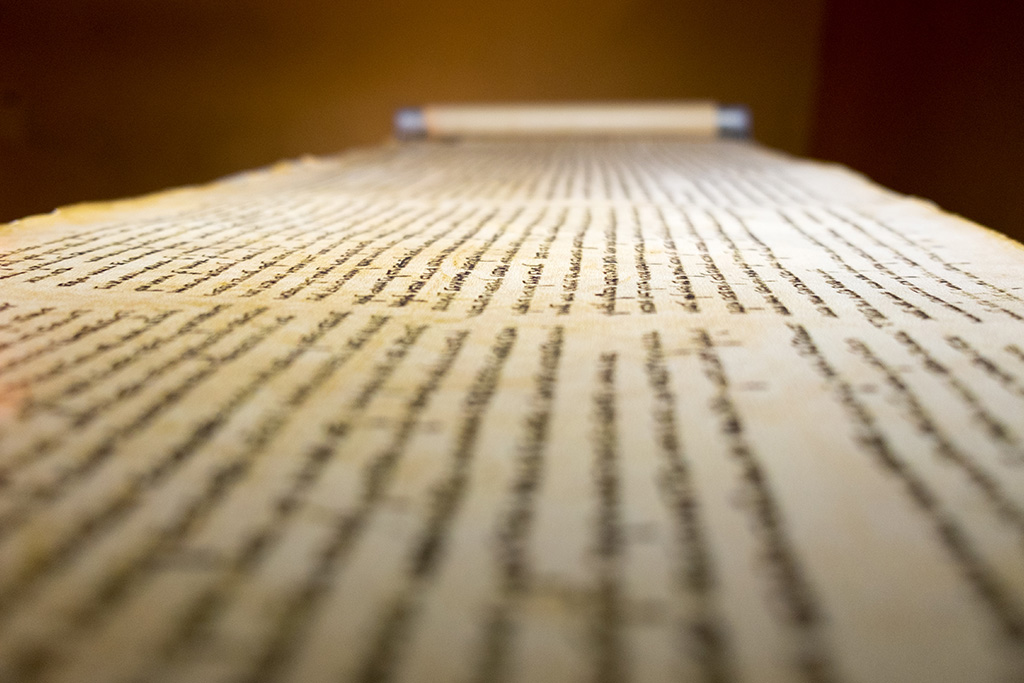

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a massive collection of ancient writings, primarily written in Hebrew. These 972 scrolls contain the oldest known copy of the Hebrew Bible. The only book that isn’t included is Esther. And while the Dead Sea Scrolls predate the Masoretic text (the authoritative Rabbinic Hebrew Scriptures) of the Hebrew Bible by a millennium, the two sets of manuscripts bear a remarkable resemblance–a testimony to the reliability of the Old Testament. (We’ll explore the differences in a moment).

Among the scrolls, there are more than 200 copies of Old Testament books, including 39 copies of Psalms, 33 copies of Deuteronomy, and 24 copies of Genesis. Additionally, there are hundreds of extrabiblical writings from the Second Temple period.

Some of them are small, like ancient post-it notes. One is over 29 feet long. While more than three quarters of the scrolls are in Hebrew, the remainder are written in Aramaic and Greek.

The vast majority of these texts were written on animal skin, using black carbon-based ink or red ink made from a mineral called cinnabar. DNA testing revealed that the animal skins used were goat, calf, antelope, and ibex. Some scholars note that there appears to be a correlation between the type of animal hide used and the significance of the scroll. One scroll is even made of copper. (Scholars have appropriately named it “Copper Scroll.”)

While the biblical scrolls we can compare to the Masoretic text are undeniably valuable, one of the most significant aspects of the scrolls’ discovery is that they also offer a much-needed lens into the Second Temple period.

“The Scrolls give us a tremendous amount of further information about that period,” says Dr. Lawrence Schiffman of Yeshiva University. “Until the Scrolls were discovered, we relied on the books of Josephus and the books of Maccabees.”

How Old are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

Until that stone was thrown into one of the caves in 1947, the Dead Sea scrolls appear to have remained undisturbed for millennia. Scholars have employed a variety of methods to determine roughly how old the scrolls actually are.

After analyzing the writings and comparing them to other texts, Jewish scholar Dr. Frank Moore Cross and archaeologist Nahman Avigad concluded that the scroll fragments were written between 225 BC and 50 AD. Carbon dating estimated that an animal skin from the scrolls was from around the same period. And bronze coins found around the caves appear to span from 135 BC to AD 73.

American theologians Dr. James C. Vanderkam and Dr. Peter Flint were part of the main team working on the scrolls, and after reviewing the evidence, they concluded that we have “strong reason for thinking that most of the Qumran manuscripts belong to the last two centuries BCE and the first century CE.”

The latest of the bronze coins is from the Jewish-Roman war, and it’s believed that the scrolls were hidden away in the Qumran caves during this period.

Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?

Most scholars believe the Dead Sea Scrolls were written by a Jewish sect known as the Essenes, who are described in the works of Flavius Josephus. The scrolls and caves they were found in give hints that suggest this was the work of the Essenes; however, they could have been written and preserved by another Jewish sect living in the area.

Josephus describes an Essene ceremony for new members that has a lot in common with an initiation ceremony discussed in a scroll called “Community Rule.” That scroll also refers to sharing property, which Josephus tells us the Essenes did. (Although other groups, such as the early Christians, shared property as well.)

Perhaps the most compelling piece of evidence in support of the Essene theory came from the first-century geographer, Pliny the Elder. He specifically identified a group of Essenes living in the desert near the northwest shore of the Dead Sea. The Qumran caves are about a mile from the northwest shore.

Still, there isn’t a scholarly consensus about the origin of the scrolls. Some scholars are willing to concede that they came from a Jewish sect living in the area (the discovery of Jewish ritual baths makes a pretty strong case for this), but they won’t go so far as to identify a particular sect, such as the Essenes, as the group responsible for the scrolls.

More recently, Dr. Lawrence Schiffman has suggested that the community was led by Zadokite priests, making them Sadducees. His evidence? One scroll has a calendar that dates festivals according to the Sadducees’ calendar. Another describes purity laws that exactly match other writings of the Sadducees.

Are the Dead Sea Scrolls Different Than the Bible?

As we noted earlier, the Dead Sea Scrolls contain copies of all but one of the books in the Hebrew Bible–Esther. But the majority of the scrolls aren’t part of the biblical canon. They’re hymns, liturgies, wisdom writings, commentaries expanding on Jewish law, apocrypha, and other extra biblical writings.

Still, there are some notable differences between the Old Testament texts we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic text, which our copies of the Old Testament have been based on for centuries.

Textual Variants Between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Masoretic Text

Some of these textual variants are subtle, and may not make much difference to modern readers. One example is the height of Goliath. The Masoretic text says he was six cubits and a span–over nine feet tall. The Dead Sea Scrolls say he was four cubits and a span–about six feet, six inches tall. Whether or not Goliath was giant by both ancient and modern standards doesn’t have much bearing on how we interpret the text—either way, Goliath was so big that nobody wanted to face him in single combat.

“At the meaning level, most of the variants are not important,” says Dr. James Vanderkam, a Dead Sea Scroll scholar.

But sometimes the Dead Sea Scrolls don’t just provide slightly different details–they include information we don’t find in the Masoretic text that can affect interpretation. For example, in Genesis, God asks Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. The account in the Dead Sea Scrolls offers an explanation why.

“The Qumran text attempts to ‘soften the blow of God’s action’ by introducing a Satan figure, called ‘Mastemah’ or ‘prince of malevolence,’ who goads God into the test,” Vanderkam says in an interview with U.S. News & World Report. “God thus does not originate the evil but merely countenances it and permits Abraham to prove his faithfulness.”

The scrolls also contain more prophecies from Ezekiel, Jeremiah, and Daniel that weren’t in the Masoretic text, as well as fifteen extra psalms attributed to David and Joshua. These more substantial textual variants present a question for scholars: which manuscript is the true, unaltered Word of God?

Do the Dead Sea Scrolls Provide a Reliable Biblical Manuscript?

The chief editor of the Dead Sea Scrolls’ biblical texts, Dr. Eugene Ulrich, believes the scrolls are evidence that there were multiple variations of the Hebrew Bible existing simultaneously, all of which were equally treated as Scripture. (He expounds on this theory in his book, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Origins of the Bible.)

Others are more hesitant to make such strong claims, but biblical books contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls share some variations with the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible that predates the Masoretic text.

Jesuit scholar Joseph Fitzmyer points out the implications: “the differences in the Septuagint are no longer considered the result of a poor or tendentious attempt to translate the Hebrew into the Greek; rather they testify to a different pre-Christian form of the Hebrew text.”

But while some variants in the manuscripts are minor, the major differences still challenge scholars to make a decision.

“If it could be demonstrated we have two biblical traditions arising independently of one another, instead of one being a revision or corruption of the other, then which one are you going to call God’s Word?” asks Old Testament scholar Dr. John Walton. As an editor of multiple Bible editions, including the NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, Walton holds a skeptical view of the Dead Sea Scrolls’ biblical authority.

While scholars don’t unanimously agree on who wrote the scrolls, one thing is clear: it was probably a specific Jewish sect. Did they have the authority to determine what did and didn’t belong in the canon for the larger Jewish community?

“The sectarians also did not have a clear delineation of the boundary between ‘biblical’ and ‘non-biblical’ books,” says professor Timothy Lim. “For them, authoritative scriptures consist of the traditional biblical books, but also other ones that were left out of the Protestant and Jewish canons, but included in the Catholic and Orthodox canons (e.g. book of Jubilees, book of Enoch). Moreover, there were other scriptures, not included in any contemporary canon, that they considered authoritative.”

What Do the Dead Sea Scrolls Say About Jesus?

The scrolls don’t mention Jesus, but one scroll has come to be known as the “Son of God” text, and its mysterious wordings have led to multiple interpretations. For Christians, the phrase “Son of God” would seem to be a clear reference to Jesus, as it’s used throughout the Synoptic gospels. But Roman emperors were sometimes called the “son of God,” too.

Here’s how scrolls scholars Michael Wise, Martin Abegg, and Edward Cook translate the scroll in A New Translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls (sections in brackets were damaged):

“He will be called the son of God, they will call him the son of the Most High. But like the meteors that you saw in your vision, so will be their kingdom. They will reign only a few years over the land, while people tramples people and nation tramples nation. Until the people of God arise; then all will have rest from warfare. Their kingdom will be an eternal kingdom, and all their paths will be righteous. They will judge the land justly, and all nations will make peace. Warfare will cease from the land, and all the nations shall do obeisance to them. The great God will be their help, He Himself will fight for them, putting peoples into their power, overthrowing them all before them. God’s rule will be an eternal rule and all the depths of [the earth are His].

“[. . . ] [a spirit from God] rested upon him, he fell before the throne. [. . . O ki]ng, wrath is coming to the world, and your years [shall be shortened . . . such] is your vision, and all of it is about to come unto the world. [. . . Amid] great [signs], tribulation is coming upon the land. [. . . After much killing] and slaughter, a prince of nations [will arise . . .] the king of Assyria and Egypt [. . .] he will be ruler over the land [ . . .] will be subject to him and all will obey [him.] [Also his son] will be called The Great, and be designated his name.”

Unfortunately, we don’t have the complete scroll — part of it was too damaged to even piece together from fragments. This leaves scholars with an incomplete puzzle, and a debate that may never be resolved. Is the “son of God” referenced here a messianic figure, or a king propped up as some sort of a false god? While scholars can make an argument for either case, according to Wise, Abegg, and Cook, most believe that the “son of God” referred to here is not a messianic figure, and therefore, not Jesus.

Still, the Dead Sea Scrolls contain all but one of the Old Testament books. These books are full of messianic prophecies that are fulfilled in Jesus.

How Did Scholars Find the Dead Sea Scrolls?

When Bedouin shepherds accidentally stumbled into the first Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947, they didn’t know what they had. They eventually sold three of these priceless artifacts to a dealer for seven pounds–the equivalent of less than $30.

These initial scrolls made their way into the hands of Hebrew University. Mar Samuel of the Syrian Orthodox Church purchased the remaining four scrolls, and waited for a more opportune moment to resell them.

Dr. John Trever from the American School of Oriental Research (ASOR) noticed similarities between the original scrolls and the oldest known biblical manuscript, the Nash Papyrus. And then it took about two years for anyone to rediscover that first Qumran cave.

ASOR archaeologists and Bedouins simultaneously (and separately) hunted the surrounding area for more artifacts. By 1956, they’d found 11 Qumran caves containing scrolls, over 900 scrolls, and tens of thousands of scroll fragments. (In 2017, a 12th cave was found, but it had already been looted.)

Mar Samuel put up an ad in The Wall Street Journal to sell his four scrolls in 1954. “Biblical manuscripts dating back to at least 200 BC are for sale. This would be an ideal gift to an educational or religious institution or group.” They were purchased by Hebrew archaeologists for $250,000 (about $2.2 million today) and brought to Jerusalem.

Very few of the more than 900 scrolls were completely intact. The vast majority have been carefully reassembled over several decades from tens of thousands of fragments.

How Were the Dead Sea Scrolls Studied?

Imagine playing Scrabble in ancient Hebrew. Now imagine that your pieces deteriorate the more you handle them. Each scroll is a puzzle, with hundreds of delicate pieces of parchment that have to fit together physically and textually.

Most of the fragments were acquired by the Palestine Archaeological Museum, where scholars began assembling, translating, and studying them. One might think archaeologists and scholars would go to great lengths to preserve these priceless documents, but that was far from the case. Writer Yossi Krausz puts it best:

“Unfortunately, the original work on the Scrolls actually caused a great deal of damage to the fragile parchment. Scholars smoked while studying the fragments, and taped them together using regular tape. Part of the ongoing conservation work seeks merely to reduce the damage done by scholars of the past, who may have destroyed more in a few years than had been lost over the previous 2,000.”

Many of the scrolls we have today bear little resemblance to the ones that were first found. Thankfully, the early scholars diligently photographed every piece. Dr. Larry Schiffman explains what it’s like to study the scrolls now:

“There is a stage where you need the physical scrolls, because of letters around the edge or other things like that,” he says. “But mostly, the photos are much better, because of the use of infrared technology. Some of the Scrolls have become completely brown and are not decipherable to the naked eye.”

In the early days, only a small group of scholars had access to the scrolls — or even photos of the scrolls — which was one of the many ways the Dead Sea Scrolls became the center of controversy.

The Controversy Surrounding the Dead Sea Scrolls

Who “owns” the Dead Sea Scrolls? The people who find them? The people who buy them? The governments that lead the countries they’re found in? Who gets to study them first? These questions are all part of the baggage that has come with this landmark discovery.

Academic controversy

While the academic world surged with excitement, actual progress on the scrolls progressed at a very slow pace. Scholars around the globe were eager to get their eyes on the greatest archaeological discovery of the century, but only a select few had access.

The scrolls were found in 1947, and it wasn’t until the Israeli government intervened in 1990 that other scholars had access. Dr. Larry Schiffman was part of the publication team.

“The problem was that the Israelis gave the job of publication to a team of Christian scholars, who kept saying, ‘We’re almost done, we’re almost done, we’re almost done.’ That deal turned out to be a mistake,” Schiffman says. “It was clear that they just weren’t doing it. The Israeli government overturned the whole arrangement in 1990, and within a short time the Scrolls were published and exhibited.”

Political controversy

As of today, the Israeli government owns the Dead Sea Scrolls. Both Jordan and the Palestine National Authority actively dispute Israel’s claim to the scrolls.

While today the scrolls are located in the Israel Museum, they were originally housed and studied in the Palestinian Archaeological Museum, known today as the Rockefeller Museum. Jordan claims that Israel illegally seized the scrolls during the Six Day War for Israel’s independence. When the scrolls are toured in other countries, Jordan still demands those countries to return the scrolls to them, not Israel.

Israel says Jordan never legally owned them because they had no right to occupy Israel or claim its artifacts.

Palestine claims the scrolls were “removed from Palestinian territories” and therefore illegally acquired.

Pnina Shor of the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA) says, “We are the custodians of the Dead Sea Scrolls. As such, we have a right to exhibit them and to conserve them.”

So far, foreign governments have always returned the scrolls to Israel after displaying them.

What Is Happening with the Dead Sea Scrolls Today?

Scholars are still actively studying the scrolls, but now anyone can join them in studying the scrolls. The scrolls themselves are publicly displayed in museums around the world. And through a partnership with Google, the Israeli Antiquities Authority have also archived them online in high-resolution images in the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

You can see the technology behind the project in this video by the IAA:

What the Dead Sea Scrolls Mean to Modern Christians

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls didn’t render our Bibles obsolete. For the most part, it didn’t even change the way we read our Bibles. But these texts give us an important look into a little-known period of Judaism that stretched into Jesus’ lifetime and beyond.

The scrolls also give us confidence in the reliability of the Jewish scribes who faithfully preserved Scripture. And while the textual variants show a manuscript that didn’t make it into the Jewish canon, the Dead Sea Scrolls remain a valuable artifact for biblical scholars to examine the ancient foundations of today’s Scriptures.

Read 15 surprising facts about the Dead Sea Scrolls, Dead Sea Scroll myths, and get a visual summary with the Dead Sea Scrolls infographic.