Can I Trust My Bible?

Technology has changed so many things that we used to take for granted. It wasn’t so long ago that people invested hundreds of dollars in sets of encyclopedias; by the time they were paid for, a lot of the information in those books was obsolete. Today the vast majority of us carry in our pockets a tool with immediate access to almost any information we can possibly imagine: our phones

Past generations of curious kids asked their parents about the world, and those answers were typically considered unquestionable truth. It wasn’t until they were older that they realized that sometimes their parents may not have had all the answers. Now kids can fact-check their parents in real time by Googling every answer they give.

In this technologically advanced climate, it’s natural that questions arise about whether or not we can still trust the Bible. Can we trust this ancient book to inform us about history, about who we are, and more importantly, about who God is? Is the Bible trustworthy and accurate, or is it simply a collection of ancient fables?

Where Did the Bible Come From?

If we want to judge the trustworthiness of Scripture, we need to consider its origins. Where did it come from and how did it take the form we commonly think of as “the Bible”?

The word we use to describe the books that belong in Scripture is “canon.” “Canon” comes from a Greek word that describes a straight bar that a carpenter would use for measurement or to check whether something was straight and true. Therefore, the books in the biblical canon are those writings that measure up to the strict standard of Scripture.

As many critics of the Bible will protest, there are many books that claim to be just as legitimate as the books in our Bible. How can we actually know which books deserve to be Scripture and which don’t? After all, we’re looking at books written by a variety of authors in all kinds of settings over thousands of years.

The Hebrew Canon

Imagine sitting in a synagogue in the first century. Over in the corner, the rabbi has a collection of scrolls. He probably doesn’t have all the scrolls that will eventually make up the Old Testament, but he has quite a few. As a library of holy books, they’re not organized in any particular order. It isn’t until the scrolls are bound together into books that a legitimate sequence will be decided upon.

There was no definitive Hebrew canon in the first century, but that doesn’t mean that there was no consensus on what was and wasn’t considered authoritative. By the time Jesus was born, Scripture was basically broken into three sections: the law, the prophets, and the writings. And while there was some question about which writings were authentic, the books that were considered authoritative weren’t much different than the ones we have now.

Of the 39 Old Testament books, most are directly quoted as Scripture by New Testament authors. Even when Old Testament books aren’t directly cited, there are often allusions to them. For instance, no one quotes Jonah, but Jesus does mention him (Matthew 12:40). And while Judges is never directly cited, the book of Hebrews mentions many of the judges by name.

This means that readers of the gospels and epistles would have had an implicit understanding of an unofficial Hebrew canon—even though it hadn’t been concretely established. The Hebrew canon wouldn’t be distinctively established until the council of Jamnia in the late first century.

In the end, the authoritative Hebrew canon would be comprised of 24 books—the same ones recognized by Protestants. You might be wondering why there’s such a discrepancy, since Protestants acknowledge 39 Old Testament books. The difference can be explained this way:

| Hebrew Bible | Protestant Bible |

| Shemuel | 1 and 2 Samuel |

| Melakhim | 1 and 2 Kings |

| Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles) | 1 and 2 Chronicles |

| Ezra-Nehemiah | Ezra, Nehemiah |

| Trei Asar (The Twelve) | Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi |

As we can see, many books that are considered one book in the Hebrew canon are broken into multiple books in the Protestant Bible. So even though the book count doesn’t match, the actual writings do.

The New Testament Canon

In the beginning of the church, the gospel message was shared orally. People who had followed Jesus, witnessed his miracles, and experienced his death and resurrection went to various towns and shared these events by retelling the stories about and teachings of Jesus. Obviously during this time, the teachings of Jesus’ apostles were given considerable weight, since these men spent so many years learning at his feet.

Can We Trust Oral Tradition?

While it’s popular for skeptics to call into question the trustworthiness of the oral tradition that undergirded the books of the Bible, there are reasons why we can have confidence in the reliability of oral teachings.

One of the most prominent criticisms of the early church’s oral transmission of the gospel is that there’s too much information to pass on accurately. But experts in oral tradition have discovered many lengthy oral epics from Central Asia and Africa that have remained remarkably static over time.

When we look at the Gospels in light of the orally dominant world from which they came, we recognize many reliable hallmarks of the oral tradition. In general, it is incredibly consistent when it comes to message and content, despite minor differences in order of events and wordings.

It would be wrong to assume that people in the early church who communicated the Gospels via oral tradition were not interested in accuracy. The apostles were very concerned that people understood the origin and importance of the stories they were hearing:

For we did not follow cleverly devised stories when we told you about the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ in power, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty. He received honor and glory from God the Father when the voice came to him from the Majestic Glory, saying, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.” We ourselves heard this voice that came from heaven when we were with him on the sacred mountain. —1 Peter 1:16–18

The apostles weren’t risking their lives to pass on myths and fables.

The Gospel was Recorded

As the church continued to grow, some factors made writing down the gospel story inevitable. More and more Christians were seeking to fulfill their responsibility to take the gospel into Rome and Asia Minor. To maintain the purity of the narrative (especially in light of the apostles’ advancing age and mortality), it became essential to write down the gospel story.

In the end, we didn’t just end up with one Gospel. We ended up with 4 distinct versions that would be recognized as Scripture: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These books communicate the gospel story in a way that gives us a more complete view of Christ.

The Gospel of Matthew

Date written: late 50s, early 60s AD

Written for a more specifically Hebrew audience, Matthew’s gospel focused on demonstrating how Jesus’ ministry fulfilled Old Testament prophecies of the coming Messiah.

The Gospel of Mark

Date written: mid- to late-50s AD

Leaving out a lot of the Hebrew-specific elements of the gospel, Mark’s Gospel told Jesus’ story in a way that would have communicated well to Gentiles. He focused on Christ’s humanity.

The Gospel of Luke

Date written: Likely after 62 AD but before 67 AD

Along with Acts, Luke wrote his Gospel for Theophilus, who was evidently a gentile of some renown. This Gospel writer focused on communicating a detailed and ordered account of Christ’s ministry, passion, and resurrection.

The Gospel of John

Date written: 70–100 AD

This gospel writer focused on the theological implications of Jesus’ story. John shone a light on what Jesus intended to communicate about himself.

We can’t be certain when the Gospels were written; the dates attributed to them are based on educated guesses. For instance, there is some question as to how closely in time Luke’s Gospel and the book of Acts were written. If they were written together, they would have needed to be completed after the events of Acts 28 in 62 AD. But they probably would have been written prior to Paul’s martyrdom (64–67 AD), otherwise Luke would have included this important part of Paul’s story in his account of the early church. Ultimately, since we can’t be sure how long before Acts Luke’s Gospel was written, it’s difficult to date accurately.

If you’re interested in an in-depth look at the authorship of the Gospels, take a look at the Zondervan Academic post, “Who Wrote the Gospels, and How Do We Know for Sure?”

The Writing of the Epistles

As these Gospels were recorded, Paul’s influence was growing in the early church. His conversion from church persecutor to Christian convert was dramatic, but still required input from the apostles.

In his letter to the Galatians, Paul discussed his first trip to Jerusalem to stay with Peter:

Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Cephas and stayed with him fifteen days. I saw none of the other apostles—only James, the Lord’s brother. —Galatians 1:18–19

He then discussed his second trip to meet with the apostles:

Then after fourteen years, I went up again to Jerusalem, this time with Barnabas. I took Titus along also. I went in response to a revelation and, meeting privately with those esteemed as leaders, I presented to them the gospel that I preach among the Gentiles. I wanted to be sure I was not running and had not been running my race in vain. —Galatians 2:2

Paul submitted himself to the authority of the apostles to ensure that the gospel he was preaching would pass muster. They responded with their approval:

James, Cephas and John, those esteemed as pillars, gave me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship when they recognized the grace given to me. They agreed that we should go to the Gentiles, and they to the circumcised. —Galatians 2:9

This stamp of approval made Paul an apostle to the Gentiles and fast-tracked the church’s acceptance of Paul’s authority. So, when he began writing letters to churches he was overseeing, his letters were immediately accepted as authoritative. Early into the second century, churches were copying and distributing his letters among themselves—along with the gospels of the apostles.

An approximate chronological list of Paul’s epistles looks like this:

Galatians: 48 AD

1 Thessalonians: 51–52 AD

2 Thessalonians: 51–53 AD

1 Corinthians: 53–55 AD

2 Corinthians: 55–56 AD

Romans: 57 AD

Philippians: 60 AD

Ephesians: 62 AD

Colossians: 62 AD

Philemon: 62 AD

1 Timothy: 63–64 AD

Titus: 63–64 AD

2 Timothy: 66 AD

The General Epistles and Revelation

Along with the gospels and Paul’s writings, the New Testament features other assorted epistles and finishes with an apocalyptic vision from the apostle John. While there’s some scholarly disagreement about the authorship and date for some of these books, they typically break down this way:

James

Date: 44–45 AD

Historically accepted as having been written by James, the brother of Jesus and leader in the Jerusalem church (Acts 15).

1 Peter

Date: 62–63 AD

Peter named himself as the author of this letter (1:1). There is still some debate about the book’s authorship based on the perception that Peter would have been a largely uneducated fisherman. But that’s not an overly convincing argument, especially in light of the fact that Peter acknowledged the help he received with the epistle:

“With the help of Silas, whom I regard as a faithful brother, I have written to you briefly, encouraging you and testifying that this is the true grace of God. Stand fast in it.” —1 Peter 5:12

2 Peter

Date: 65–68 AD

It’s generally been accepted that Peter wrote the second epistle attributed to him, but some debate has sprung up regarding Petrine authorship. In these discussions, it’s important to remember that the early church rejected many letters that were falsely attributed to apostles. We shouldn’t be too quick to assume that we’re more stringent in vetting New Testament authorship than were the early church fathers.

Hebrews

Date: Before 70 AD

Despite much debate, there is no consensus on the authorship of Hebrews. Throughout history, it has been at various times attributed to different pillars of the church such as Paul, Luke, Apollos, and Clement.

Jude

Date: 64–65 AD

There’s not a lot of disagreement about the authorship of Jude. He names himself, the brother of James and (servant of) Jesus, as the author (1:1).

1, 2, and 3 John

Date: Before 98 A.D.

There is little question that 1 and 2 John were written by an author named John. Many scholars have asserted that they were likely written by the apostle and author of the fourth Gospel. In 3 John the author introduces himself as “the elder,” which is similar to the intro to 2 John. While it’s possible that “the elder” could be indicative of any church leader, it’s commonly accepted that all three of these epistles were written by the apostle John.

Revelation

Date: 95–96 AD

This book begins with a revelation of a vision given to John, but it doesn’t necessarily claim Johannine authorship. There is some discussion about whether this is not actually John the apostle but rather “John the elder”—who also would have written 2 and 3 John. But details such as the fact that the author identifies Jesus as the Logos (the “Word,” John 1:1, 1:14, Revelation 19:13) and the true witness (John 5:31–47, Revelation 2:13; 3:14) seems to point to the apostle John as the author.

Putting Together the New Testament Canon

As we saw previously in this post with the Hebrew Scriptures, the early church began recognizing the authority of the New Testament Scriptures long before an official canon was ever declared.

In the middle of the third century, the early church father Origen may have given us the earliest list of the 27 books that make up the New Testament (there’s some debate over manuscripts and whether Revelation is mentioned). Athanasius gives us an unequivocal listing in 367 AD and the Third Council of Carthage approved the same list in 397.

The truth is that, thanks to the Marcionite crisis, the canon was all but decided by the middle of the second century.

Marcion was a well-to-do member of the Roman church who fell under the influence of Gnostics. It was Marcion’s belief that Paul had utterly rejected the Law of Moses, and Marcion wanted to establish a uniquely Christian scripture void of all the Judaistic trappings.

Marcion began compiling a canon made up of 10 of Paul’s letters and a highly edited version of Luke’s Gospel. In response to Marcion, the church began to establish the authority of the four Gospels and all 13 of Paul’s letters, and started compiling a list of approved writings.

Can We Trust the Copying Process?

“Remember,” cynics will remind us, “the printing press didn’t show up until the 15th century. How can anyone guarantee that all of those hand-copied versions of the Bible were dependably accurate?”

To answer this objection, consider this: few question the accuracy of Homer’s Iliad. It’s interesting to note that there were about 500 years between the original Iliad and the first copy—and only 643 copies of the manuscript exist. The accuracy for those copies is about 95 percent.

By way of contrast, we have more than 5,800 copies of Greek New Testament manuscripts with less than 100 years between the time the copies were written. The accuracy between copies is about 99.5 percent—and this doesn’t count all of the copies we have in the Syriac, Coptic, and Aramaic languages.

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls was a manuscript of Isaiah that was approximately 1,000 years older than any other previously discovered manuscript. The text of the two copies was nearly identical. The faith of biblical scribes contributed mightily to the exacting nature of their work. They weren’t simply doing a job; they were reproducing the living Word of God.

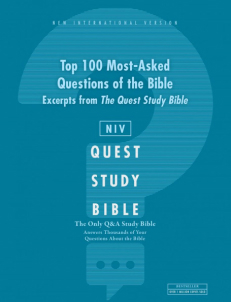

Can I Have Confidence in Modern Translations?

One argument that seems to rear its head occasionally is the idea that modern translations such as the NIV are based upon corrupt Greek and Hebrew texts. This argument charges that the manuscripts used by modern translators were tainted by false theologies like Arianism and Gnosticism.

While there are definitely a few textual variations in some manuscripts, they don’t typically challenge the meaning of the text. For instance, simple spelling differences are to blame for 70 percent of variations in Greek texts.

The extremely few variations that actually cause any change to the meaning of the text make up less than one percent of all textual variations—and don’t call into question any key Christian doctrines.

For instance, in 1 John 1:4 there is some debate over whether the text reads one of two ways:

“We write this to make our joy complete.”

“We write this to make your joy complete.”

There are manuscripts that contain either version. And just like they do in English, these two Greek words differ by only one letter. When we read 1 John 1:4 in the New International Version, the discrepancy is pointed out in the notes.

We Can Definitely Trust the Bible

This is a brief overview of some fairly involved topics. But the deeper we look into the origin of the canon and our various biblical manuscripts, the stronger our faith in God’s Word becomes. Not only do we see God’s fingerprints in the biblical text itself, but we catch glimpses of his concern and involvement in maintaining the integrity and purity of Scripture through time.

Additional articles you might find helpful:

3 Common Arguments Against Trusting the Bible.

Why Translating the Bible Is More Tough than You Think.