The Commission for an Accurate, Understandable Version of the Bible

“The translation shall be designed to communicate the truth of God’s revelation as effectively as possible to English readers in the language of the people.”

—NIV Translators’ Manual, November 1968

On August 27, 1965, the broad evangelical community issued a commission for an accurate and understandable version of the Bible in contemporary English. Though it had taken years to acquire the support necessary to issue the mandate, the real work was only beginning. It would be another 13 years before people could hold in their hands a complete Bible.

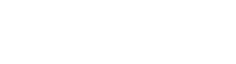

A committee of 15 scholars was elected to oversee the process and the work of more than 100 translators. Known as the Committee on Bible Translation (CBT), its members were experts in the various languages, eras and books of the Bible. They came from denominations across the spectrum of evangelicalism, from seminaries and universities across the country.

Committee on Bible Translation, 1966

• E. Leslie Carlson, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

• Edmund P. Clowney, Westminster Theological Seminary

• Ralph Earle, Nazarene Theological Seminary

• Burton L. Goddard, Gordon Divinity School

• R. Laird Harris, Covenant Theological Seminary

• Earl S. Kalland, Conservative Baptist Theological Seminary (Denver)

• Kenneth S. Kantzer, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

• Robert Mounce, Bethel College (St. Paul)

• Stephen W. Paine, Houghton College

• Charles F. Pfeiffer, Central Michigan University

• Charles C. Ryrie, Dallas Theological Seminary

• Francis R. Steele, North Africa Mission

• John H. Stek, Calvin Theological Seminary

• John C. Wenger, Goshen Biblical Seminary

• Marten H. Woudstra, Calvin Theological Seminary

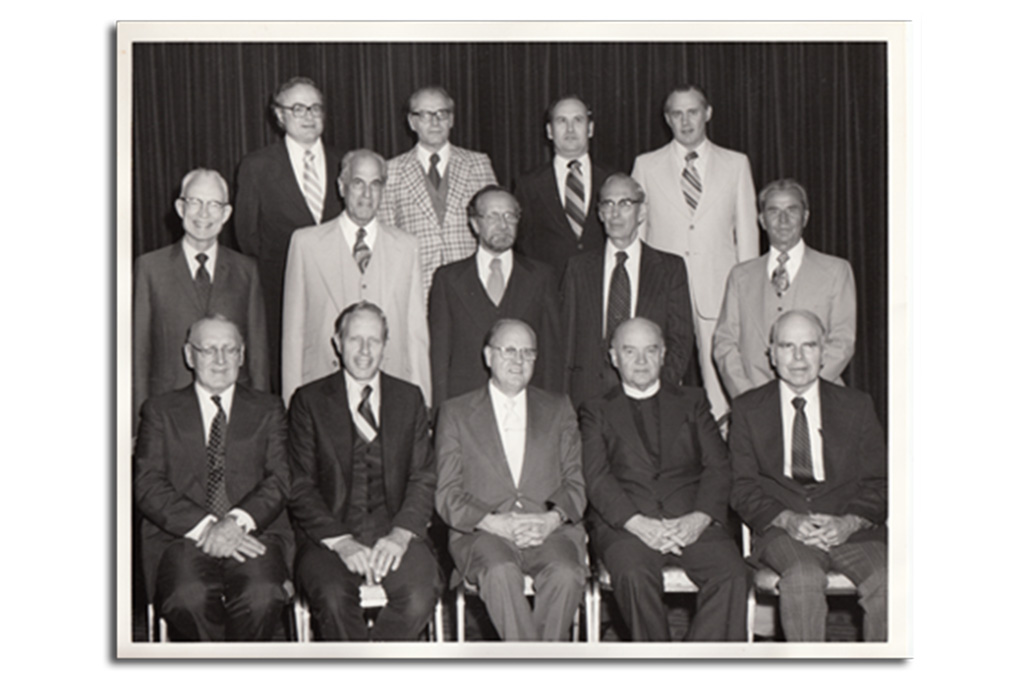

While a distinct effort was made to create a diverse committee, every person on the committee was committed to the authority and truthfulness of Scripture, as was every translator who would work on the Bible. They were required to sign a statement of faith, affirming “The Bible alone, and the Bible in its entirety, is the Word of God written, and is therefore inerrant in the autographs” or a similar confession or creed.

Left: Every one of the 100-plus translators was required to sign a statement of belief. Right: Youngve Kindberg (left), president of the New York Bible Society International, with Ed Palmer, Executive Secretary of the CBT, at a CBT meeting in Liberty Corner, NJ.

Left: Every one of the 100-plus translators was required to sign a statement of belief. Right: Youngve Kindberg (left), president of the New York Bible Society International, with Ed Palmer, Executive Secretary of the CBT, at a CBT meeting in Liberty Corner, NJ.

The committee had other guidelines, but the heart of the matter was producing a translation that would be accurate and clear as well as capturing the beauty and dignity of Scripture. To fulfill these objectives, the translators had to start fresh with the original Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

But before the translation work could begin, it had to be funded. Christian publishers and other organizations had expressed little concrete interest in providing the necessary financial support. In what many considered an act of God, the New York Bible Society (now Biblica) stepped in.

Society members Youngve Kindberg and Morris Townsend had attended an early planning session in 1966 and were struck by the realization that such a translation would benefit the society’s evangelism efforts.

After months of planning with the CBT, the society’s board formally agreed in January 1968 to provide funding for the project, estimating overall expenses at $850,000. The CBT would control the translation, and the New York Bible Society would control the copyright.

Following in the footsteps of Martin Luther’s Bible and the King James Version, the work would be done in stages and reviewed by committees.

• Three to five translators, plus an English stylist, were assigned to a portion of Scripture for the initial translation according to their areas of expertise.

• Manuscripts were then sent to the Intermediate Editorial Committee, the General Editorial Committee and, lastly, the CBT, which would approve every word in the final translation.

Checks and rechecks, peer reviews, stylist reviews, additional checks, proofs: The process would be thorough. Edwin Palmer, a pastor, ex-Marine and instructor of systematic theology at Westminster Theological Seminary, agreed to come on board full time as the CBT executive secretary to manage it.

Work began with the Gospel of John. The CBT prepared examples for the translators using Exodus 1-9, 15 and Acts 1-10. A variety of Greek texts would be consulted for the New Testament translation. For the Old Testament, translators would start with the Masoretic Text in the latest editions of Biblia Hebraica.

As with many projects, the beginning was filled with challenges. Committees had to figure out how to function effectively and efficiently, and they had to set up basic editorial standards. How should they handle footnotes? Should there be a comma before the last item in a series? What is the standard for units of measurement? Paragraph lengths?

A Translation Blossoms, One Passage at a Time

“The aim shall be to make the translation represent as clearly as possible only what the original says, and not to inject additional elements by unwarranted paraphrasing.”

—NIV Translators’ Manual, November 1968

Committee reviews were brutal. Every word was scrutinized. After the CBT’s review of the first three chapters of John, its list of questions for John 1:14 in one round included, among others:

• Is John speaking of only grace here? Or of truth and grace?

• We must be very sure here and at 1:18 and 3:16 that monogenēs is best translated by Son and not by begotten or the like.

• Should it be “came” or “became”?

• “Man” is clearer but is this what John said?

• Why capitalize the adjective “Only”?

Eventually the verse would be published as: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

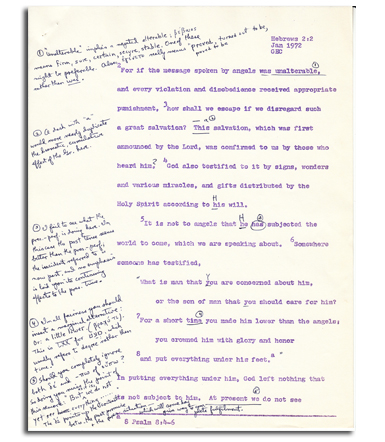

Notes on Hebrews 2 from the General Editorial Committee in January 1972.

Notes on Hebrews 2 from the General Editorial Committee in January 1972.

Eventually the verse would be published as: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

When Ed Palmer first received the full translation of John, he didn’t know what to think of it. It was freer and clearer than anything he had ever seen. But was it accurate?

“Having lived with it for several weeks, I believe that we are in the process of having a very exciting translation,” Palmer wrote to the CBT members. “Part of my fear was due to my unawareness of the great variety of meaning of many Greek words.”

Faithfulness in translation has two parts. A translation must be faithful to the original text, or else it will not convey the original meaning, but it must also be faithful to the target language, or else the meaning will not be understood. Words have nuances and multiple meanings. At times, word-for-word translation may not be as accurate as a unit-of-thought to unit-of-thought translation.

To create a version that was both faithful and comprehensible, the translators had to achieve a balance between a literal, word-for-word translation style, known as formal equivalence, and a freer, thought-for-thought translation known as dynamic or functional equivalence.

The CBT was willing to depart from the original Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek structure of a sentence to ensure the text was in proper English. But if it wasn’t necessary to shift the syntax, the original structure would be kept.

Disagreements were inevitable. But whether or not a particular argument won the day, everyone had to trust that the Lord was directing the project. Praying for God’s wisdom and guidance, those who worked on the project fervently believed he would use their efforts for his glory.

A profound sense of humility was essential. As Martin Luther said about his own efforts to translate the Bible, “It is good for me, for otherwise I might have died with the fond persuasion that I was learned.”

The work was intense and methodical, but the pursuit of a shared goal kept the atmosphere collegial. And there were undeniable benefits to such a thorough process. Distinct theological or personal beliefs could be caught. Idiosyncrasies of the individual translator could be smoothed over. Any word that was too American or too British could be spotted and changed.

The process also ensured that the translators met the other main goal of the translation—readability for the average speaker of modern English.

Healthy Debate

“Every effort shall be made to achieve good English style.”

—NIV Translators’ Manual, November 1968

“Scholars are notoriously poor writers,” translator Bruce Waltke admitted. “We use words that nobody else can understand.”

To help bridge the gap between scholar and reader, stylists were consulted every step of the way. They helped to ensure proper flow in the texts, as well as adherence to proper grammar and the guidelines set out by the CBT. They helped to make lofty thoughts accessible.

Margaret Nicholson Smith was one of the principal stylists. A longtime editor at Oxford University Press, she was an expert in modern language usage and had an eye for English style. Frank Gaebelein, another primary stylist, was known for interrupting discussions with, “You can’t say it that way.”

Translator Donald Burdick, an expert in Greek, was always quick to reply. “Well, the Greek doesn’t say it that way.”

“Then how about this?”

“No, that won’t work either.”

Debate would continue until eventually both parties could say: Yes, this is faithful to the original and good English.

“There wasn’t any tension, any hostility,” Waltke said. “The stylist would just keep asking, ‘How about this? Would this be its meaning?’”

Style notes from Frank Gabelein on Philippians 1, Intermediate Editorial Committee, August 1971.

To test their work with other audiences, translator Burton Goddard asked freshman and sophomores at a Massachusetts high school to read the translation of John and mark any words or phrases they did not understand. Words such as “sheepfold” and “ascend” caught their eye. Pastors and church members also shared their thoughts throughout the project on portions of the Scripture.

By the end of 1969, the Gospel of John was ready for its public debut. The New York Bible Society published it in paperback as The Gospel According to John: A Contemporary Translation.

The book soon began to spread through the evangelical community. Current CBT member Karen Jobes remembers receiving a copy from a friend in college. “The Gospel of John reminded me that Jesus loves me,” Jobes said. “It turned my spiritual life around.” Only when she joined the CBT did Jobes realize that the version of the Gospel she received was part of what is now known as the NIV.

Although A Contemporary Translation, or ACT, had been adopted for the Gospel of John, the CBT and the New York Bible Society felt the label wasn’t simple enough. In the late 1960s, names such as The Holy Bible: Common English Version, The Holy Bible: A Contemporary English Translation, and The Holy Bible: International Translation had also been considered, but none of those names felt right, either.

When a proposal was made for New International Bible: A Contemporary Translation, the groups knew they were getting close. “International” spoke to their original goal of a Bible for all English-speaking people.

Work proceeded on all books of the Bible, but the CBT’s goal was to release the New Testament as soon as possible to build support for the full translation. The New York Bible Society was running low on funds. Original estimates had been way off, and fundraising was not keeping up.

Before the New Testament could be released, however, a name had to be finalized and one more group needed to weigh in. Zondervan Publishers, which would publish the New Testament, responded to the proposal with a recommendation: The Holy Bible: The New International Version. The name fit. In 1973, New Testament: The New International Version was published.

A Translation In Crisis

“The finished product shall be suitable for use in public worship, in the study of the Word, and in devotional reading.”

—NIV Translators’ Manual, November 1968

The Old Testament translation work continued, with the CBT meeting every summer for weeks at a time to review recommendations, check and revise the text, and approve any final manuscripts. Often, the meeting location was in a foreign country such as Scotland, Greece or Spain, where lodging and food were cheap and distractions were minimal.

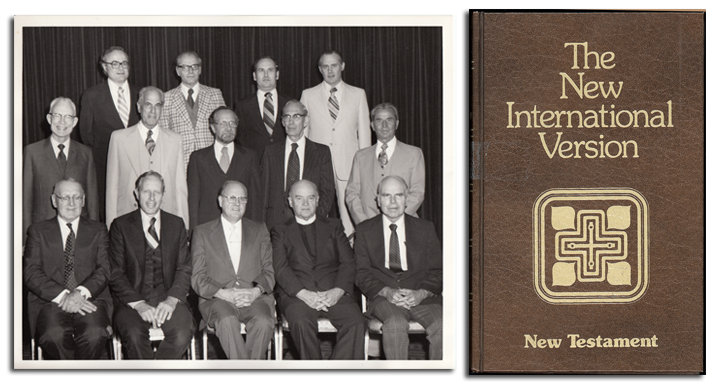

Left: Members of the CBT in the 1970s. Right: The Holy Bible: The New International Version was published in its entirety in 1978.

Left: Members of the CBT in the 1970s. Right: The Holy Bible: The New International Version was published in its entirety in 1978.

But by 1975, the issue of funding reached a crisis point. The New York Bible Society had reduced its staff, drained its endowment, taken out loans and put its beautiful New York building up for sale. It was out of funds and out of options.

To come this far and not finish was unthinkable. The positive response to the New Testament showed that the English-speaking world desperately wanted a reliable Bible in contemporary language.

The CBT estimated that finishing the Old Testament would take two to four years. To speed up the process, it split the review committee in two and brought in additional scholars. The New York Bible Society sought out Pat Zondervan, head of Zondervan Publishers in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His company was already involved with the NIV as publishers of the New Testament. Would it consider funding the rest of the translation?

Zondervan’s answer was yes. The publisher already had exclusive rights in the United States and would advance the society up to $250,000 in royalties to finish the work.

In 1978, the full version of the NIV Bible hit the presses, published by Zondervan in the United States and Hodder & Stoughton in the United Kingdom. A plethora of NIV resources followed, including commentaries, concordances, handbooks and the groundbreaking NIV Study Bible, which included more than 20,000 study notes.

The NIV could be a Bible for pastors, scholars and believers of any age, to be used in daily devotions and academic studies, in the pulpit and on the streets, in Sunday schools and seminary classrooms. The only thing left to do was to get the Word into their hands.